Soyuz 1

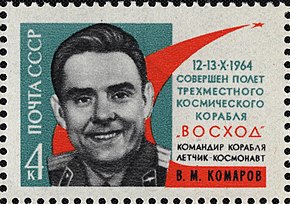

1964 commemorative stamp of Vladimir Komarov | |

| Mission type | Test flight |

|---|---|

| Operator | Experimental Design Bureau (OKB-1) |

| COSPAR ID | 1967-037A |

| SATCAT no. | 02759 |

| Mission duration | 1 day 2 hours 47 minutes 52 seconds |

| Orbits completed | 18 |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Spacecraft | Soyuz 7K-OK No.1 |

| Spacecraft type | Soyuz 7K-OK |

| Manufacturer | Experimental Design Bureau (OKB-1) |

| Launch mass | 6450 kg |

| Landing mass | 2800 kg |

| Dimensions | 10 m long (with solar panels) 2.72 m wide |

| Crew | |

| Crew size | 1 |

| Members | Vladimir Komarov |

| Callsign | Рубин (Rubin – "Ruby") |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | 23 April 1967, 00:35:00 GMT |

| Rocket | Soyuz 11A511 s/n U15000-04 |

| Launch site | Baikonur, Site 1/5[1] |

| Contractor | Experimental Design Bureau (OKB-1) |

| End of mission | |

| Landing date | 24 April 1967, 03:22:52 GMT |

| Landing site | 3 km west of Karabutak, Orenburg Oblast, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union[2] |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Geocentric orbit |

| Regime | Low Earth orbit |

| Perigee altitude | 197.0 km |

| Apogee altitude | 223.0 km |

| Inclination | 50.8° |

| Period | 88.7 minutes |

Soyuz 1 (Russian: Союз 1, Union 1) was a crewed spaceflight of the Soviet space program. Launched into orbit on 23 April 1967 carrying cosmonaut colonel Vladimir Komarov, Soyuz 1 was the first crewed flight of the Soyuz spacecraft. The flight was plagued with technical issues, and Komarov was killed when the descent module crashed into the ground due to a parachute failure. This was the first in-flight fatality in the history of spaceflight.

The original mission plan was complex, involving a rendezvous with Soyuz 2 and an exchange of crew members before returning to Earth. However, the launch of Soyuz 2 was called off due to thunderstorms.

Crew

[edit]| Position | Cosmonaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Pilot | Second and last spaceflight | |

Backup crew

[edit]| Position | Cosmonaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Pilot | ||

Mission parameters

[edit]- Mass: 6,450 kg (14,220 lb)

- Perigee: 197.0 km (122.4 mi)

- Apogee: 223.0 km (138.6 mi)

- Inclination: 50.8°

- Period: 88.7 minutes

Background

[edit]Soyuz 1 was the first crewed flight of the first-generation Soyuz 7K-OK spacecraft and Soyuz rocket, designed as part of the Soviet lunar program. It was the first Soviet crewed spaceflight in over two years, and the first Soviet crewed flight following the death of the Chief Designer of the space programme Sergei Korolev. Komarov was launched on Soyuz 1 despite failures of the previous uncrewed tests of the 7K-OK, Kosmos 133 and Kosmos 140. A third attempted test flight was a launch failure; a launch abort triggered a malfunction of the launch escape system, causing the rocket to explode on the pad. The escape system successfully pulled the spacecraft to safety.[3]

According to interviews with Venyamin Russayev, a former KGB agent, prior to launch, Soyuz 1 engineers are said to have reported 203 design faults to party leaders, but their concerns "were overruled by political pressures for a series of space feats to mark the anniversary of Lenin's birthday".[4] Russayev also claims that Yuri Gagarin was the backup pilot for Soyuz 1, and was aware of the design problems and the pressures from the Politburo to proceed with the flight. He attempted to "bump" Komarov from the mission, knowing that the Soviet leadership would not risk a national hero on the flight.[5] At the same time, Komarov refused to pass on the mission, even though he believed it to be doomed. He explained that he could not risk Gagarin's life.[5] Russayev's account, however, has been seen as implausible and exaggerated by most historians of the Soviet space programme.[6]

Mission planners intended to launch a second Soyuz flight the next day carrying cosmonauts Valery Bykovsky, Yevgeny Khrunov, and Aleksei Yeliseyev, with Khrunov and Yeliseyev scheduled to do an EVA over to Soyuz 1.

Mission details

[edit]Soyuz 1 was launched on 23 April 1967 at 00:32 GMT from Baikonur Cosmodrome carrying Komarov, the first Soviet cosmonaut to fly in space twice, in the 7K-OK No. 4 capsule.[7] Problems began shortly after launch when one solar panel failed to unfold, leading to a shortage of power for the spacecraft's systems. Komarov transmitted: "Conditions are poor. The cabin parameters are normal, but the left solar panel didn't deploy. The electrical bus is at only 13 to 14 amperes. The HF (high frequency) communications are not working. I cannot orient the spacecraft to the sun. I tried orienting the spacecraft manually using the DO-1 orientation engines, but the pressure remaining on the DO-1 has gone down to 180."[8] Further problems with the orientation detectors complicated maneuvering the craft. By orbit 13, the automatic stabilisation system was completely dead, and the manual system was only partially effective.

The crew of Soyuz 2 modified their mission goals, preparing themselves for a launch that would include fixing the solar panel of Soyuz 1. However, that night, thunderstorms at Baikonur affected the booster's electrical system, causing the mission to be called off.[9]

As a result of Komarov's report during the 13th orbit, the flight director decided to abort the mission. After 18 orbits, Soyuz 1 fired its retrorockets and reentered the Earth's atmosphere. Despite the technical difficulties up to that point, Komarov might still have landed safely. A few minutes before the tragedy, Komarov maintained radio contact with Gagarin, in particular, stating: "The engine was running for 146 seconds. Everything is going fine. Everything is going fine! The ship was oriented correctly. I am in the middle chair. Tied with straps."[10] To slow the descent, first the drogue parachute was deployed, followed by the main parachute. However, due to a defect, the main parachute did not unfold; the exact reason for the main parachute malfunction is disputed.[11][12]

Komarov then activated the manually deployed reserve chute, but it became tangled with the drogue chute, which did not release as intended. As a result, the Soyuz descent module fell to Earth in Orenburg Oblast almost entirely unimpeded, at about 40 m/s (140 km/h; 89 mph). A rescue helicopter spotted the descent module lying on its side with the parachute spread across the ground on fire. The retrorockets then started firing which concerned the rescuers since they were supposed to activate a few moments prior to touchdown. By the time they landed and approached, the descent module was in flames with black smoke filling the air and streams of molten metal dripping from the exterior. The entire base of the capsule burned through. By this point, it was obvious that Komarov had not survived, but there was no code signal for a cosmonaut's death, so the rescuers fired a signal flare calling for medical assistance. Another group of rescuers in an aircraft then arrived and attempted to extinguish the blazing spacecraft with portable fire extinguishers. This proved insufficient and they instead began using shovels to throw dirt onto it. The descent module then completely disintegrated, leaving only a pile of debris topped by the entry hatch. When the fire at last ended, the rescuers were able to dig through the rubble to find Komarov strapped into the center couch, his body had turned into charred clothing and flesh. Doctors pronounced the cause of death to be from multiple blunt-force injuries. The body was transported to Moscow for an official autopsy in a military hospital where the cause of death was verified to match the field doctors' conclusions.

The Soyuz 1 crash site coordinates are 51°21′39″N 59°33′45″E / 51.3609°N 59.5624°E, which is 3 km (1.9 mi) west of Karabutak, about 275 km (171 mi) east-southeast of Orenburg. There is a memorial monument at the site in the form of a black column with a bust of Komarov at the top, in a small park on the roadside.[2][13][14]

Posthumously, Komarov was named a Hero of the Soviet Union for the second time, and awarded the Order of Lenin. He was given a state funeral, and his ashes were interred in the Kremlin Wall Necropolis at Red Square, Moscow.[4]

Eight years after Komarov's death, a story began circulating that Komarov cursed the engineers and flight staff, and spoke to his wife as he descended,[15] and these transmissions were received by an NSA listening station near Istanbul.[16] Historians such as Asif Azam Siddiqi regard this to be untrue.[16][17] Komarov's final recorded words appear to have been a conversation with a tracking station located near Simferopol on the topic of the separation of the Soyuz modules just before reentry,[18] with the final message received being "Спасибо, передайте всем Произошло" ("Thank you, tell everyone it happened") [Garbled].[18][19]

Legacy

[edit]The Soyuz 1 tragedy delayed the launch of Soyuz 2 and Soyuz 3 until 25 October 1968. This 18-month gap, with the addition of the explosion of an uncrewed N-1 rocket on 3 July 1969, scuttled Soviet plans of landing a cosmonaut on the Moon. The original mission of Soyuz 1 and Soyuz 2 was ultimately achieved by Soyuz 4 and Soyuz 5.

A much improved Soyuz programme emerged from this eighteen-month delay, mirroring the improvements made in the Apollo program after the Apollo 1 tragedy. Although it failed to reach the Moon, the Soyuz went on to be repurposed from the centrepiece of the Zond lunar program to the people-carrier of the Salyut space station program, the Mir space station, and the International Space Station. Although it suffered another tragedy with the Soyuz 11 accident in 1971, and went through several incidents with non-fatal launch aborts and landing mishaps, it has become one of the longest-lived and most dependable crewed spacecraft yet designed.

Komarov is commemorated in two memorials left on the lunar surface: one left at Tranquility Base by Apollo 11,[20] and the Fallen Astronaut statue and plaque left by Apollo 15.

References

[edit]- ^ "Baikonur LC1". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Archived from the original on 15 April 2009. Retrieved 4 March 2009.

- ^ a b "Google Maps – Soyuz 1 Crash Site – Memorial Monument Photo". Retrieved 25 December 2010.

- ^

Part 1 – Soyuz in Mir Hardware Heritage by David S. F. Portree.

Part 1 – Soyuz in Mir Hardware Heritage by David S. F. Portree.

- ^ a b "24 April 1967: Russian cosmonaut dies in space crash". On This Day. BBC. 24 April 1967. Retrieved 15 April 2009.

- ^ a b "Cosmonaut Crashed Into Earth "Crying In Rage": Krulwich Wonders..." NPR.org. 18 March 2011. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- ^ "A Cosmonaut's Fiery Death Retold". NPR.org. 11 May 2011. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

- ^ "Vladimir Komarov's tragic flight aboard Soyuz-1". www.russianspaceweb.com. Retrieved 26 December 2022.

- ^ Kamanin Diary, 23 April 1967

- ^ French, Francis; Burgess, Colin (2007). In the Shadow of the Moon. University of Nebraska Press. p. 177.

- ^ Milkus, Alexander (24 April 2017). "Трагедия «Союза-1»: Почему разбился космонавт Владимир Комаров" [The Soyuz-1 Tragedy: Why Cosmonaut Vladimir Komarov Crashed]. kp.ru (in Russian). Archived from the original on 6 March 2024. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- ^ "The Red Stuff". friends-partners.org. 24 October 2000. Archived from the original on 17 March 2014. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- ^ "The Soyuz-1 accident investigation". Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ^ "Google Maps – Soyuz 1 Crash Site – Memorial Monument Location". Retrieved 25 December 2010.

- ^ "Google Maps – Soyuz 1 Crash Site – Memorial Monument Photo closeup". Retrieved 25 December 2010.

- ^ "Soyuz 1". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Archived from the original on 20 August 2016. Retrieved 15 April 2009.

- ^ a b Krulwich, Robert (5 May 2011). "A Cosmonaut's Fiery Death Retold". npr.org. Archived from the original on 3 May 2019.

- ^ French, Francis; Burgess, Colin (2007). In the Shadow of the Moon. University of Nebraska Press. p. 181.

- ^ a b Siddiqi, Asif (2020). Soyuz 1 The Death of Vladimir Komarov Pressure, Politics, and Parachutes. SpaceHistory101.com Press. pp. 36–37. ISBN 9781887022958.

- ^ Siddiqi, Asif (2020). Soyuz 1 The Death of Vladimir Komarov Pressure, Politics, and Parachutes. SpaceHistory101.com Press. p. 73. ISBN 9781887022958.

- ^ Aldrin, Buzz; McConnell, Malcolm (1989). Men from Earth. Bantam. ISBN 978-0-553-05374-6.