Lucien Carr

Lucien Carr | |

|---|---|

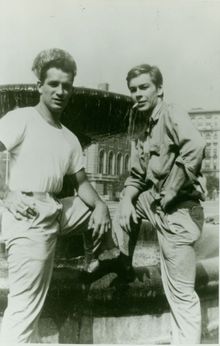

Jack Kerouac and Carr (right) in 1944 | |

| Born | March 1, 1925 New York City, US |

| Died | January 28, 2005 (aged 79) Washington, D.C., US |

| Education | Phillips Academy Bowdoin College University of Chicago Columbia University |

| Spouses | Francesca von Hartz

(m. 1952; div. 1963)

|

| Children | 3, including Caleb Carr |

Lucien Carr (March 1, 1925 – January 28, 2005) was a key member of the original New York City circle of the Beat Generation in the 1940s and also a convicted manslaughterer. He later worked for many years as an editor for United Press International.

Early life

[edit]Carr was born in New York City; his parents, Marion Howland (née Gratz) and Russell Carr, were both children of socially prominent St. Louis families. His maternal grandfather was Benjamin Gratz, a St. Louis capitalist who was engaged in the rope making business and was descended from Michael Gratz, who was among the first Jewish settlers of Philadelphia and was prominent in Philadelphia's social life.[1][2][3][4][5] After his parents separated in 1930, young Lucien and his mother moved back to St. Louis; Carr spent the rest of his childhood there.[6]

At the age of 12, Carr met David Kammerer (b. 1911), a man who would have a profound influence on the course of his life. Kammerer was a teacher of English and a physical education instructor at Washington University in St. Louis. Kammerer was a childhood friend of William S. Burroughs, another scion of St. Louis wealth who knew the Carr family. Burroughs and Kammerer had gone to primary school together, and as young men they traveled together and explored Paris's nightlife: Burroughs said Kammerer "was always very funny, the veritable life of the party, and completely without any middle-class morality."[7] Kammerer met Carr when he was leading a Boy Scout Troop[8] of which Carr was a member, and quickly became infatuated with the child.

Over the next five years, Kammerer pursued Carr, showing up wherever the young man was enrolled at school. Carr would later insist, as would his friends and family, that Kammerer had been hounding Carr sexually with a predatory persistence that would today be considered stalking.[9] Whether the attentions of a man fourteen years his senior were frightening or flattering to the underage Carr is now a matter of some debate among those who chronicle the history of the Beat Generation.[10] What is not in dispute is that Carr moved quickly from school to school: from the Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, to Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine, to the University of Chicago, and that Kammerer followed him to each one.[11] The two of them socialized on occasion. Carr always insisted, and Burroughs believed, that he never had sex with Kammerer; Jack Kerouac biographer Dennis McNally wrote that Kammerer "was a Doppelgänger whose sexual desires Lucien would not gratify; their connection was an intertwined mass of frustration that hinted ominously of trouble."[12]

Carr's University of Chicago career abruptly ended after he put his head into a gas oven. He explained away this act as a "work of art,"[13] but the apparent suicide attempt, which Carr's family believed was catalyzed by Kammerer, led to a two-week stay in the psychiatric ward at Cook County hospital.[14] Carr's mother, who had moved to New York City, brought her son there and enrolled him at Columbia University, close to her home.[citation needed]

If Marion Carr had sought to distance her son from David Kammerer, she did not succeed. He soon quit his job and followed Carr to New York, moving into an apartment on Morton Street in the West Village, one block from William Burroughs' residence; the two older men remained friends.[15]

Columbia and the Beats

[edit]As a freshman at Columbia, Carr was recognized as an exceptional student with a quick, roving mind. A fellow student from Lionel Trilling's humanities class described him as "stunningly brilliant. ... It seemed as if he and Trilling were having a private conversation."[16] He joined the campus literary and debate group, the Philolexian Society.[17]

It was also at Columbia that Carr befriended Allen Ginsberg in the Union Theological Seminary dormitory on West 122nd Street (an overflow residence for Columbia at the time), when Ginsberg knocked on the door to find out who was playing a recording of a Brahms trio.[13] Soon after, a young woman Carr had befriended, Edie Parker, introduced Carr to her boyfriend, Jack Kerouac, then twenty-two and nearing the end of his short career as a sailor. Carr, in turn, introduced Ginsberg and Kerouac to one another[18] – and both of them to his older friend with more first-hand experience at decadence: William Burroughs. The core of the New York Beat scene had formed, with Carr at the center. As Ginsberg put it, "Lou was the glue."[19]

Carr, Kerouac, Ginsberg and Burroughs explored New York's grimier underbelly together. It was at this time that they fell in with Herbert Huncke, an underworld character and later writer and poet. Carr had a taste for provocative behavior, for bawdy songs and for coarse antics aimed at shocking those with staid middle-class values. According to Kerouac, Carr once convinced him to get into an empty beer keg, which Carr then rolled down Broadway. Ginsberg wrote in his journal at the time: "Know these words, and you speak the Carr language: fruit, phallus, clitoris, cacoethes, feces, foetus, womb, Rimbaud."[13] It was Carr who first introduced Ginsberg to the poetry and the story of 19th century French poet Arthur Rimbaud. Rimbaud would be a major influence on Ginsberg's poetry.[19]

Ginsberg was plainly fascinated by Carr, whom he viewed as a self-destructive egotist but also as a possessor of real genius.[20] Fellow students saw Carr as talented and dissolute, a prank-loving late-night reveler who haunted the dark pockets of Chelsea and Greenwich Village until dawn, without making a dent in his brilliant performance in the classroom. On one occasion, asked why he was carrying a jar of jam across the campus, Carr simply explained that he was "going on a date." Returning to his dorm in the early hours another morning to find that his bed had been short-sheeted, Carr retaliated by spraying the rooms of his dorm-mates with the hallway fire-hose – while they were still sleeping.[21]

Carr developed what he called the "New Vision," a thesis recycled from Emersonian transcendentalism and Parisian Bohemianism[22] which helped undergird the Beats' creative rebellion:

- Naked self-expression is the seed of creativity.

- The artist's consciousness is expanded by derangement of the senses.

- Art eludes conventional morality.[23]

For ten months, Kammerer remained a fringe member of this simmering crowd, still utterly infatuated with Carr, who sometimes avoided him and on other occasions indulged Kammerer's attentions. On one occasion he may even have brought Kammerer to a session of Trilling's class.[21] Accounts of this period report that Kammerer's presence and lovelorn devotion to Carr made many of the other Beats uncomfortable.[24] On one occasion, Burroughs found Kammerer trying to hang Kerouac's cat.[25] Kammerer's psyche was evidently decaying; he was barely scraping by, helping a janitor clean his building on Morton Street in exchange for rent.[26] In July 1944, Carr and Kerouac began talking about shipping out of New York on a Merchant Marine vessel, a scheme which drove Kammerer frantic with anxiety at the possibility of losing Carr. In early August, Kammerer crawled into Carr's room via the fire escape and watched him sleep for half an hour; he was caught by a guard as he crawled back out again.[27]

Killing in Riverside Park

[edit]On August 13, 1944, Carr and Kerouac attempted to ship out of New York to France on a merchant ship. They were aiming to fulfill a fantasy of travelling across France in character as a Frenchman (Kerouac) and his deaf-mute friend (Carr) and hoped to be in Paris in time for the liberation by the Allies. Kicked off the ship by the first mate at the last minute, the two men drank together at the Beats' regular hangout, the West End Bar. Kerouac left first and bumped into Kammerer, who asked where Carr was; Kerouac told him.[28]

Kammerer caught up with Carr at the West End, and the two men went for a walk, ending up in Riverside Park on Manhattan's Upper West Side.[29]

According to Carr's version of the night, he and Kammerer were resting near West 115th Street when Kammerer made yet another sexual advance. When Carr rejected it, he said that Kammerer assaulted him physically, and gained the upper hand in the struggle due to his larger size. In desperation and panic, Carr said, he stabbed the older man by using a Boy Scout knife from his St. Louis childhood. Carr then tied his assailant's hands and feet, wrapped Kammerer's belt around his arms, weighted the body with rocks, and dumped it in the nearby Hudson River.[26]

Next, Carr went to the apartment of William Burroughs, gave him Kammerer's bloodied pack of cigarettes, and explained the incident. Burroughs flushed the cigarettes down the toilet and told Carr to get a lawyer and to turn himself in. Instead, Carr sought out Kerouac, who with the aid of Abe Green (a protégé of Herbert Huncke) helped him dispose of the knife and some of Kammerer's belongings before the two went to a movie (Zoltan Korda's The Four Feathers) and to the Museum of Modern Art to look at paintings.[30] Finally, Carr went to his mother's house and then to the office of the New York District Attorney, where he confessed. The prosecutors, uncertain whether the story was true or whether a crime had even been committed, kept him in custody until they had recovered Kammerer's body. Carr identified the corpse and led police to where he had buried Kammerer's eyeglasses in Morningside Park.[26]

Kerouac, who was identified in The New York Times coverage of the crime as a "23-year-old seaman", was arrested as a material witness, as was Burroughs, whose father posted bail. However, Kerouac's father refused to post the $100 bond to bail him out. In the end, Edie Parker's parents agreed to post the money if Kerouac would marry their daughter. With detectives serving as witnesses, Edie and Jack were married at the Municipal Building,[31] and after his release, he moved to Grosse Pointe Park, Michigan, Parker's hometown. Their marriage was annulled in 1948.[32]

Carr was charged with second-degree murder. The story was closely followed in the press since it involved a well-liked, gifted student from a prominent family, New York's premier university, and the scandalous elements of rape and homosexuality.[24] The newspaper coverage embraced Carr's story of an obsessed homosexual preying on an appealing heterosexual younger man, who finally lashed out in self-defense.[29] The Daily News called the killing an "honor slaying", an early example of what was later called the 'gay panic defense.'[33] If there were subtle shadings to the tale of Carr's five-year saga with Kammerer, the newspapers ignored them.[34] Carr pleaded guilty to first-degree manslaughter, and his mother testified at a sentencing hearing about Kammerer's predatory habits. Carr was sentenced to a term of one to twenty years in prison. He served two years in the Elmira Correctional Facility in Upstate New York and was released.[24]

Carr's Beat crowd (which Ginsberg called "the Libertine Circle") was, for a time, shattered by the killing. Several members sought to write about the events. Kerouac's The Town and the City is a fictional retelling, in which Carr is represented by the character "Kenneth Wood." A more literal depiction of events appears in Kerouac's later Vanity of Duluoz. Soon after the killing, Allen Ginsberg began a novel about the crime, which he called The Bloodsong, but his English instructor at Columbia, seeking to preclude more negative publicity for Carr or the university, persuaded Ginsberg to abandon it.[24] According to the author Bill Morgan in his book The Beat Generation in New York, the Carr incident also inspired Kerouac and Burroughs to collaborate in 1945 on a novel entitled And the Hippos Were Boiled in Their Tanks, which was published for the first time in its entirety in November 2008.[35]

The 2013 film Kill Your Darlings is a fictionalized account of the killing in Riverside Park that tells a version of the murder similar to the version that is portrayed in And the Hippos Were Boiled in Their Tanks. In the film, Kammerer is portrayed as deeply in love with Carr to the point of obsession. Carr is portrayed as a young man who is very conflicted by his feelings towards Kammerer and struggles to break ties. Their relationship is further complicated by Carr using Kammerer to write his school essays and Kammerer using the essays to stay attached to Carr.

Dissenting opinions

[edit]In a letter to New York magazine, published on June 7, 1976, Patricia Healy (née Goode), the wife of the Irish writer T. F. Healy, put forth a strident defense of Kammerer. Her letter was a rebuttal to an article by Aaron Latham that had appeared in the magazine. She had been a student at Barnard College while the Beat Generation was coalescing in the 1940s in New York City. At the time, she knew several key members of that literary movement, including Burroughs, Kerouac, and Carr, but not Ginsberg.

In her rebuttal, she painted a radically different portrait of Kammerer (with whom she said she had been particularly close) and his relationship with Carr. Refuting the common depiction of Kammerer as fringe figure within the Beat movement, she characterized him as a guiding light within that literary circle. She said his informal lectures had inspired many of the Beats, particularly Kerouac, whom she accused of ingratitude for never acknowledging his debt to Kammerer. She discredited what she termed "the Lucien myth," that Carr had been the victim of Kammerer's relentless obsession and stalking. On the contrary, she asserted it was Kammerer who wanted to be rid of Carr, whom he referred to as "that little bastard." On one occasion, she wrote, she accompanied Carr to Kammerer's apartment, where he hostilely told Carr never to come around again. The resulting altercation culminated with Kammerer punching the younger man and knocking him to the floor. Healy's letter also hinted that Carr had frequently sought Kammerer's help in writing his Columbia term papers.

Healy also maintained that Kammerer—far from his frequent depiction as a homosexual predator—was very much heterosexual, as evidenced, she said, by his pursuit of a "kept woman" of his acquaintance.[36]

In Carr's obituary in The Guardian (February 8, 2005), Eric Homberger questioned Carr's account of the killing:

Central to Carr's defence was that he was not gay, and that Kammerer, an obsessive stalker, threatened sexual violence. Once the story of a predatory homosexual was presented in court, Carr became a victim and the murder was framed as an honor killing. There was no one in court to question the story or offer a different version of the relationship.

Much of the story, however, is doubtful; perhaps now, with Carr's death, it may be possible to disentangle the strands of insinuation, legal spin and lies. There is no independent proof that Kammerer was a predatory stalker; there is only Carr's word for the pursuit from St. Louis to New York. There is persuasive evidence that Kammerer was not gay. Carr enjoyed his ability to manipulate the older man, and got him to write essays for his classes at New York's Columbia University. A friend remembers Kammerer slamming the door of his apartment in Carr's face, and telling him to get lost.

There is much evidence to suggest that Carr had been a troubled and unstable young man. While at the University of Chicago, he attempted to commit suicide with his head in an unlit gas oven, and told a psychiatrist that it had been a performance, a work of art. In New York, Carr gave Ginsberg, who had been raised respectably in New Jersey, where his father was a teacher, a new language of eroticism and danger. Ginsberg carefully wrote in his journal the key terms of the "Carr language": fruit, phallus, clitoris, cacoethes, faeces, foetus, womb, Rimbaud.[37]

Settling down

[edit]After his prison term, Carr went to work for United Press (UP), which later became United Press International (UPI), where he was hired as a copy boy in 1946. He remained on good terms with his Beat friends, and served as best man when Kerouac impetuously married Joan Haverty in November 1950.[38] Carr has sometimes been credited with having provided Kerouac with a roll of teleprinter paper "pilfered" from the UP offices, on which Kerouac then wrote the entire first draft of On the Road in a 20-day marathon fueled by coffee, speed, and marijuana.[19] The scroll was real, but Carr's share of this first draft tale is probably a conflation of two different episodes; the 119-foot first roll, which Kerouac wrote in April 1951, was actually many different large sheets of paper trimmed down and taped together. After Kerouac finished that first version, he moved briefly into Carr's apartment on 21st Street, where he wrote a second draft in May on a roll of United Press teleprinter, and then transferred that work to individual pages for his publisher.[39]

Carr remained a diligent and devoted employee of UP / UPI. In 1956, when Ginsberg's "Howl" and Kerouac's On the Road were about to be national sensations, Carr was promoted to night news editor.[citation needed]

Leaving behind his youthful exhibitionism, Carr came to cherish his privacy. In one well-noted gesture, Carr asked Ginsberg to remove his name from the dedication at the start of "Howl." The poet agreed.[40] Carr even became a voice of caution in Ginsberg's life, warning him to "keep the hustlers and parasites at arm's length."[29] For many years, Ginsberg would visit the UPI offices and press Carr to cover the various causes with which Ginsberg had allied himself.[19] Carr continued to serve Kerouac as a drinking buddy, a reader and critic, reviewing early drafts of Kerouac's work and absorbing Kerouac's growing frustrations with the publishing world.[citation needed]

Carr married Francesca von Hartz in 1952, and the couple had three children: Simon, Caleb, and Ethan (in 1994, Caleb published The Alienist, a novel which became a best-seller.) They divorced and he later married Sheila Johnson.[37]

"When I met him in the mid-50s," wrote jazz musician David Amram, Carr "was so sophisticated and worldly and fun to be with that even while you always felt at home with him, you knew he was always one step ahead and expected you to follow." According to Amram, Carr remained loyal to Kerouac to the end of the older man's life, even as Kerouac descended into alienation and alcoholism.[41]

Lucien Carr spent 47 years, his entire professional career, with UPI, and went on to head the general news desk until his retirement in 1993. If he was famous as a young man for his flamboyant style and outrageous vocabulary, he perfected an opposite style as an editor, and nurtured the skills of brevity in the generations of young journalists whom he mentored. He was known for his oft-repeated suggestion, "Why don't you just start with the second paragraph?" [19] Carr was reputed to have strict acceptable standards for a good lede (lead paragraph), his mantra being "Make 'em laugh, make 'em cry, make 'em horny" (or variations of this).[42][43]

Carr died at George Washington University Hospital in Washington, D.C. in January 2005 after a long battle with bone cancer.[44]

See also

[edit]- Beat, a 2003 film in which Carr is portrayed by Norman Reedus.

- Kill Your Darlings, a 2013 film in which Carr is portrayed by Dane DeHaan

- Vanity of Duluoz, a semi-autobiographical novel by Kerouac, featuring Carr as the character of Claude de Maubris and Kammerer as Franz Mueller

References

[edit]- ^ "2 May 1939, Page 5 - The St. Louis Star and Times at Newspapers.com". Newspapers.com. Retrieved 2022-08-07.

- ^ Stevens, Walter Barlow (1921). Centennial History of Missouri: (the Center State) One Hundred Years in the Union, 1820-1921. S. J. Clarke publishing Company.

- ^ "Now on View: Gratz Family Artifacts Exploring American Jewish Life in Philadelphia". www.amrevmuseum.org. Retrieved 2022-08-07.

- ^ Byars, William Vincent (1916). B. and M. Gratz: Merchants in Philadelphia, 1754-1798; Papers of Interest to Their Posterity and the Posterity of Their Associates. Hugh Stephens Printing Company.

- ^ Ashton, Dianne (1996). "Barnard and Michael Gratz: Their Lives and Times (review)". American Jewish History. 84 (1): 68–69. doi:10.1353/ajh.1996.0003. ISSN 1086-3141. S2CID 161104997.

- ^ Lawlor, William, Beat Culture: Lifestyle, Icons and Impact, ABC-CLIO, 2005, p. 167

- ^ Lawlor, Beat Culture, p. 46

- ^ Caleb Carr explains this to The Daily Caller, in regards to the truth behind the movie "Kill Your Darlings", 2014, pg. 2

- ^ Adams, Frank, "Columbia Student Kills Friend and Sinks Body in Hudson River," The New York Times, August 17, 1944

- ^ For comparison, see the differences in interpretation between William Lawlor in Beat Culture and James Campbell in This is the Beat Generation, and compare to Eric Homberger's comments in "Lucien Carr: Fallen Angel of the Beat Poets"

- ^ Campbell, James, This is the Beat Generation, University of California Press, London, 1999, pp. 10–12

- ^ McNally, Dennis, Desolate Angel, Da Capo Press edition, 2003, p. 67

- ^ a b c Campbell, This is the Beat Generation, p. 12

- ^ Lawlor, Beat Culture, p. 167

- ^ Campbell, This is the Beat Generation, p. 13

- ^ Gold, Ed, "Memories of a Beat Who Took A Different Road," Downtown Express, April 1–7, 2005, Vol. 17, Number 45

- ^ "Columbia Daily Spectator 1 September 1944 — Columbia Spectator". spectatorarchive.library.columbia.edu. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- ^ Homberger, Eric, "Lucien Carr: fallen angel of the beat poets, later an unflappable news editor with United Press," The Guardian, 9 February 2005

- ^ a b c d e Hampton, Wilborn (30 January 2005). "Lucien Carr, a Founder and a Muse of the Beat Generation, Dies at 79". New York Times. Retrieved 25 May 2017.

- ^ Campbell, This is the Beat Generation, p. 23

- ^ a b Gold, "Memories of a Beat Who Took A Different Road"

- ^ Maher and Amram, Jack Kerouac, p. 117

- ^ Campbell, This is the Beat Generation, p. 26

- ^ a b c d Lawlor, Beat Culture, p. 168

- ^ McNally, Desolate Angel, p. 68

- ^ a b c Adams, "Columbia Student Kills Friend"

- ^ Charters, Ann. (1973). Kerouac: A biography, pp. 44 and 47. San Francisco, CA: Straight Arrow Press.

- ^ McNally, Desolate Angel, p. 69

- ^ a b c Homberger, "Lucien Carr: fallen angel of the beat poets"

- ^ Campbell, This is the Beat Generation, pp. 30–31

- ^ Campbell, This is the Beat Generation, p. 33

- ^ Knight, Brenda, ed., Women of the Beat Generation: The Writers, Artists and Muses at the Heart of a Revolution, Conari Press, 1996, p. 78-9.

- ^ McNally, Desolate Angel, p. 70

- ^ Campbell, This is the Beat Generation, pp. 34–35

- ^ "Grove Atlantic - An Independent Literary Publisher Since 1917". www.groveatlantic.com. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- ^ http://www.chezjim.com/Mom/beatniks.html, "ENCOUNTERS: Burroughs, Kerouac and Ginsberg"

- ^ a b Homberger, Eric (8 February 2005). "Lucien Carr". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- ^ McNally, Desolate Angel, p. 131

- ^ McNally, Desolate Angel, pp. 134–5

- ^ "The Last Beat". Columbia Magazine.

- ^ from an April 13, 2005 testimonial by Amram to Lucien following Lucien's death, available online at http://www.insomniacathon.org/rrILCTDA01.html

- ^ In Extremis: The Life of War Correspondent Marie Colvin, Lindsey Hilsum, Vintage Books, 2019

- ^ "The Last Beat".

- ^ "Newsman Lucien Carr Dies at 79," The Washington Post, January 29, 2005, p. B5

Sources

[edit]- Collins, Ronald & Skover, David, Mania: The Story of the Outraged & Outrageous Lives that Launched a Cultural Revolution (Top-Five Books, March 2013)

External links

[edit]- Literary Kicks -Lucien Carr

- Lucien Carr Papers at the Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Columbia University

- Lucien Carr at IMDb

- Lucien Carr discography at Discogs

- 1925 births

- 2005 deaths

- American male journalists

- American people convicted of manslaughter

- Beat Generation people

- Bowdoin College alumni

- Columbia College (New York) alumni

- Criminals from New York City

- Deaths from bone cancer in the United States

- Deaths from cancer in Washington, D.C.

- Elmira Correctional Facility

- Journalists from New York City

- News editors

- People from Greenwich Village

- Prisoners and detainees of New York (state)

- University of Chicago alumni